However far I go in my distrustful attitude, no actual harm will come of it, because my project won’t affect how I act, but only how I go about acquiring knowledge. […] This will be hard work, though, and a kind of laziness pulls me back into my old ways.

(Descartes, 1614, First Meditation, p. 3)

In this article, I will outline W. V. O. Quine’s thesis on the development of a naturalistic approach in epistemology and the related discussion that has emerged from his proposal. I will also present my views on this venture. The goals of this article are to explore the limits and necessary conditions of science in general and neuroscience in particular, but also to assess to what extent the scientific study of the mind can contribute to the foundation of scientific practice itself. I chose to enter into such an endeavour through the reconstitution of Quine’s arguments as formulated mainly in the articles “Epistemology Naturalized” (Quine, 1969) and “Two Dogmas of Empiricism” (Quine, 1951) and a selective review of the later literature.

Introduction

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that deals with human knowledge: what it is, how we acquire it and what we have the capacity know. The specific objective of epistemology is to address the relevant issues in the context of scientific practice, as this can be considered the field in which knowledge processes are best discernable but also the field in which epistemological perspectives have the most concrete impact. The roots of epistemology can be traced to the oldest philosophical texts, and certainly to those of Aristotle and Plato.

Enlightenment

An important development in this field of human thought arose with the work of Renè Descartes (Descartes, 1614), who tried to base all human knowledge on intuition and deductive logic. The philosophical current in which such theories of knowledge were articulated is called intuitionism or foundationalism, which is part of the wider school of thought of rationalism.

Descartes’ search for the foundations of knowledge emerged from challenging the established beliefs and the reliability of sensory experience. David Hume approached the same challenge from a different point of view, arguing that any intuition we have and our ability to reason are equally susceptible to error as our sensory experience since our interface with the world is exclusively through the senses. The source of unreliability is therefore attributed, according to Hume, to basing our intuitions on our susceptible to error senses. Therefore, Hume’s response leads to a degree of skepticism as to what we can know. Hume argued that our senses are the only way we have to know the world and that is enough for our usual needs, as long as the world is uniform and does not change suddenly (Salmon et al., 1992, p. 66). Although Hume’s position was not initially well-received (Fieser, 2011; Losee, 2001), it now holds an important place in the history of philosophy. The current that formed from this thesis is called empiricism.

The problem of deriving our intuitions from empirical observations is known as the problem of induction. The ontological component of the problem of induction concerns the fact that the concept of causality does not appear to exist in the world independent of the agent doing the reasoning; even the most stereotypical interaction between objects in the real world could evolve differently in some repetition, without us being able to distinguish the reason for this deviation. The question of discerning which processes we use to acquire knowledge forms the methodological component of the issue.

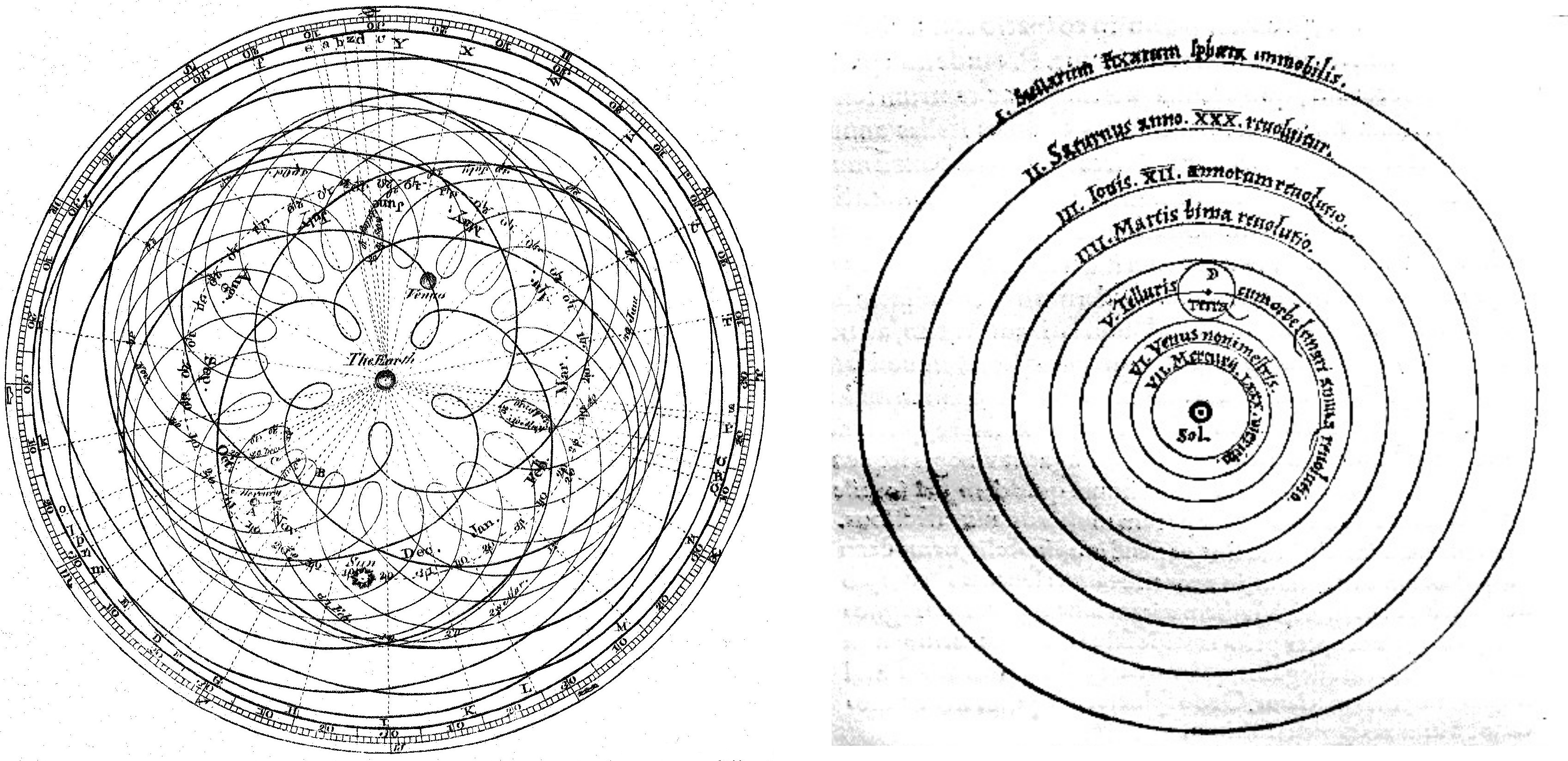

The next important milestone to the subject was the contribution of Immanuel Kant. Kant argued that we can have no sensory experience without the contribution of the mind. It is in the unchanging and universal a priori properties of the mind that we must focus our attention on to produce reliable judgements and beliefs about the world. He even suggested a series of a priori contributions of the mind to the understanding of the world, which largely derive their origin from the work of Aristotle (McCormick, 2020). He believed that these properties of the mind could be deduced using formal logic and that in combination with the innate spatio-temporal perception as well as higher logic, they can jointly enable the knowledge of the world and the construction of a coherent system of knowledge (Losee, 2001, pp. 96–97). Kant’s view was influenced by Euclidean geometry and Newton’s mechanics (Losee, 2001, p. 97), and he likened his achievement to the contribution of the Copernican revolution (McCormick, 2020).

20th century

Through their efforts to reduce mathematics to formal logic, Gotlöb Frege and Bertrand Russell devised a systematic language with which they could address older problems of epistemology. After Einstein’s theory of relativity challenged the universal validity of Newton’s theory, those philosophers who followed Frege’s and Russell’s work –the so-called “Vienna Circle”– made an attempt to use this propositional logic to dispel any metaphysics from philosophy. This historical turning point is often referred to as the “linguistic turn” in analytic philosophy. Any observational proposition would now be articulated in terms of formal logic and would have to be empirically verifiable to be considered meaningful. This requirement for any proposition to be verifiable to make sense, i.e. to not be placed in the realm of metaphysics, is known as the criterion of verifiability. The theoretical framework in which it was articulated is called the verification theory of meaning.

Under this theory it would be possible to build the set of necessary propositions on which scientific practice could be based. Kant’s proposed framework would be replaced by the network of logical relations between observational propositions and the axioms of formal logic. The scientific propositions would therefore be divided into analytic and synthetic, with the former not requiring empirical verification and being logically self-evident, and the latter being those whose meaning derives from their empirical verification. The philosophical current that followed this approach is called Logical Positivism.

The representative of Logical Positivism considered the one that got closer to the desired achievement was Rudolf Carnap (Salmon et al., 1992, p. 85). More specifically, Carnap attempted to structure an inductive logic system to the standards of Frege and Russell’s deductive logic, which would resolve the induction problem on the solid basis of formal logic. The main problem he faced was that even if he managed to complete the task at hand, Carnap would still have to prove the validity of the verifiability criterion within the system he produced to show how analytic propositions are supported. But as Kurt Gödel has shown using Hilbert’s arsenal of formal logic and mathematical formalism, there is no consistent axiomatic (mathematical) system in which its own fundamental axioms can be proved. Therefore, for Carnap to succeed, he would still have to explain the role of analytic propositions in his system without relying on the verifiability criterion.

The Carnap-Quine dispute

In his article “Empiricism, Semantics, and Ontology” (Carnap, 1950), Carnap tries to support the usefulness of the analytic propositions by separating the possible questions that could be asked into internal and external in relation to the system. Internal questions are those that can be formulated in terms of the system and answered within it; they can be either empirical questions or questions the answers to which can be directly derived with the use of logic. External questions, on the other hand, are those that cannot be explored empirically. A question could be, for example, “Are there spatio-temporal points?”. If it is articulated outside the system, its answer is a matter of convention and pragmatic faith in the system –otherwise, formulated within the system, its answer is analytic and trivial.

Quine’s critique on Carnap’s project in the much-discussed article “Two Dogmas of Empiricism” (Quine, 1951) focused on two interconnected points. First, he argued that the attempt to discriminate between analytic and synthetic sentences is artificial and vague. Such a distinction can not be supported and is not fruitful, and therefore is a metaphysical belief –exactly what the empiricists of the Vienna cycle wanted to avoid. The existence of analyticity becomes problematic as the analyticity of a sentence cannot be verified. Therefore, the criterion of verifiability, which is the cornerstone of Logical Positivism, cannot be applied. Quine considers that the doctrine of analyticity, as he calls it, is directly related to the second doctrine of Logical Positivism he identifies, that of reductionism. He even claims that the two doctrines are identical and that we are necessarily led from one to the other if we use the criterion of verifiability. He draws these conclusions by examining the different avenues that Carnap tried to follow to support the concept of analyticity: synonymy, direct definition, and explicit semantic rules, and finds them all equally ineffective and vague. In his view, as long as one is committed to empiricism one can only accept the confirmatory empirical observations as the final evidence for a proposition’s degree of truth.

Quine goes even further and presents a positive counter-proposal: he argues that “the unit of empirical significance is the whole of science” (Quine, 1951, p. 39). “The totality of our so-called knowledge or beliefs, from the most casual matters of geography and history to the profoundest laws of atomic physics or even pure mathematics and logic, is a man-made fabric which impinges on experience only along the edges.” (Quine, 1951, p. 39) The above passage presents what Quine proposed as a replacement for the two doctrines of logical empiricism –the doctrine of holism, which he attributed to Duhem (Quine, 1969, p. 267). According to this doctrine, the whole body of our empirical knowledge is tested with every new observation and no part of it is immune to revision –every “recalcitrant” observation, such that it is not compatible with existing knowledge, affects the whole system due to the interconnections between its parts. Even logic can be revised, if this is necessary to maintain the balance of this entire web. It is this interdependence of the components of our empirical knowledge that leads to the famous indeterminacy of translation (Quine, 1969, p. 267).

In his book “Word and Object” (Quine, 1960, p. 29), Quine compares the problem of the indeterminacy of translation with the analogous problem faced by the anthropologist who approaches a previously unknown tribe and tries to decipher and translate the language of the natives that is completely foreign for the anthropologist. If the sound of the word “Gavagai!” coincides with the native indicating the presence of a rabbit that suddenly jumped out of the bushes, it is reasonable for the anthropologist to assume that the word corresponds to the word “rabbit!” in his language. But based on these data alone, there are countless other equally plausible alternatives. For example, the native could have meant “a rabbit jumped out of that bush!” or “I told you it was there!”, or “a spatio-temporal blob of matter!” or simply “food!”. With just this single observation we cannot ascertain if any of these translations are correct. But as observations accumulate and as they relate to each other, possibly also with knowledge of other related languages, as is usually the case, the more confident we can be for the veracity of translation.

Therefore, a “recalcitrant” empirical observation only tells us that something in the way we interpret the world is wrong but does not tell us what. There is no one-to-one correspondence between experience and theory and therefore the error can be traced either in the auxiliary hypotheses or in the foundations of the knowledge system. It is said that theory is underdetermined by experience (Hylton & Kemp, 2020). The only way forward is to make some arbitrary choices along the way towards the full translation, which will only be verifiable and correctable based on the observations to follow. It is also reasonable to assume that concepts form in a similar way during the development of infants and during the development of science (Quine, 1969, p. 81).

Towards a naturalistic epistemology

If Quine is right to claim that the above analogy between human development and epistemology holds, this has important consequences according to him. On the one hand, the possibility of directly reducing epistemology to logic is ruled out, as an infinite number of reconstructions are in principle possible. All the advantages that such a reduction would have (which in the meantime turned into a reduction to logic in conjunction with set theory, a drastic ontological move according to him) –the “purity” of logic as reliable and self-evident, and therefore the explanation of empirical data in clearer terms, the standardization of scientific explanations, and the possible simplification of vocabulary– cannot be established (Quine, 1969, pp. 74–75). This observation leads Quine to note that the work Carnap undertook was supposed to provide a rational reconstruction, for which we would have no way of determining whether it was correct. As we have seen above, Carnap has moved away from such a pursuit by saying that the building blocks of the system are provided through conventions.

At this point Quine wonders: “But why all this creative reconstruction, all this make-believe? […] Why not settle for psychology? […] If we are out simply to understand the link between observation and science, we are well advised to use any available information, including that provided by the very science whose link with observation we are seeking to understand.” (Quine, 1969, pp. 75–76). The consequence for the fate of epistemology is, according to Quine, the following: “Epistemology in its new setting, conversely, is contained in natural science, as a chapter of psychology.” (Quine, 1969, p. 83). Quine, of course, immediately realizes the circularity of the project. However, he considers arguments against circularity pointless “once we have stopped dreaming of deducing science from observations” (Quine, 1969, p. 76). He often likens the project to Neurath’s boat (Quine, 1960, p. 3; 1969, p. 84); the aim is to reconstruct the boat while it is already floating in the middle of the sea. For Quine, the philosopher and the scientist are together on the same boat. If our goal is the “understanding of science as an institution or process in the world, and we do not intend that understanding to be any better than the science which is its object” (Quine, 1969, p. 84), then it is legitimate for this interaction to exist.

At the same time, however, he clarifies that: “Such a study could still include, even, something like the old rational reconstruction, to whatever degree such reconstruction is practicable; for imaginative constructions can afford hints of actual psychological processes, in much the way that mechanical simulations can” (Quine, 1969, p. 83). A picture of a reciprocal containment emerges: “The old epistemology aspired to contain, in a sense, natural science; it would construct it somehow from sense data. Epistemology in its new setting, conversely, is contained in natural science, as a chapter of psychology. But the old containment remains valid too, in its way. […] There is thus reciprocal containment, though containment in different senses: epistemology in natural science and natural science in epistemology.” (Quine, 1969, p. 83)

Quine identifies two consequences arising from the above: First, the problem of epistemological priority is solved, that is, whether observation –and consequently knowledge– consists of sensory data or its conscious awareness. Epistemological priority is given to what is causally closest to the sensory receptors. The problem of epistemological priority is eliminated as the concept is replaced by causal proximity (Quine, 1969, pp. 84–85). Second, the notion of the analyticity of an observational proposition can be replaced by the degree of its acceptance by the community (Quine, 1969, p. 86). The reference to subjectivity is generally eliminated as observational propositions will usually concern natural bodies (Quine, 1969, p. 87).

If we now want to define in this new context what an observational proposition is, we can say that it is a proposition “on which all speakers of the language give the same verdict when given the same concurrent stimulation. To put the point negatively, an observational proposition is one that is not sensitive to differences in past experience within the speech community” (Quine, 1969, pp. 86–87). Outside the realm of language, in that of perception there is a rather limited set of perceptual patterns, “toward which we tend unconsciously to rectify all perceptions. These, if experimentally identified, could be taken as epistemological building blocks, the working elements of experience. They might prove in part to be culturally variable, as phonemes are, and in part universal.” (Quine, 1969, p. 90).

Overview

Quine’s work is considered to have marked the end of Logical Positivism. Through Carnap’s latest writings and Quine’s writings presented above, analytic philosophy began moving towards pragmatism. It can be argued that Quine’s purpose was to save empiricism from the problems that had begun to emerge. It is clear from his texts that he wishes to maintain the criterion of verifiability, as we have seen it transform into the new picture, and he sees, like the empiricists of the Vienna Circle, physics as the model science for the construction of the new epistemology.

The metaphysical question that Quine wants to answer is how we know the world. His position is that this question can be answered through scientific research. He therefore rejects the metaphysical doctrine of the existence of some form of a priori knowledge. He is led to this metaphysical position having rejected the usefulness of a distinction between analytic and synthetic propositions, seeing scientific methodology as the only alternative approach. Therefore, he considers that this is an empirical question, which can be answered by the psychology of his time. It can be summarized as “how we reach what we call knowledge and even science from the activations of our sensory receptors”.

As Quine himself acknowledges, the question arises as to whether science is legitimized to undertake the task by its own means. The debate can be traced, to some extent, to the disagreement between Kant and Hume over what we should trust most, our senses or our reasoning. Quine brings back the dilemma proposing two new facts: first, modern science is clearly in a better position than in previous centuries to explain the apparently complex psycho-mental phenomena; second, we have ceased to seek the absolute certainty that a foundation of knowledge in logic or anything else ever tested would offer us. We will focus in turn on each of the critical issues that arise: What does the “naturalization” of epistemology mean –what does naturalism mean? How does Quine himself mean it and what other alternatives could be supported? What objections arise in the first place for the project? What is at stake in this proposed transition?

Discussion

Naturalism

Like any term, the term naturalism can carry different meanings, depending on the user, the purpose of its use and the context in which it is used. In a first sense, it may be used to indicate, as an opposition, the aversion to anything “supernatural”. Reality is limited to anything found in nature –a not-so-informative proposition (Papineau, 2020; Stroud, 1996). Almost anyone would agree with that. The first naturalists of the twentieth century already used the term to state that all information is contained in nature and so everything in it is accessible to the scientific method (Papineau, 2020). Based on these, we can distinguish two components of the term: the ontological, that is, what someone allows to be included in the “nature” they have in mind, and the methodological, what are the limits of the naturalistic approach. Although the two problems are related, we will mainly approach the latter.

Most philosophers who support the adoption of naturalism in epistemology seem to agree with the rejection of every a priori knowledge and even every a priori epistemological principle (Kitcher, 1992; Rosenberg, 1996). The qualification of the scientific methodology and empirical research follows from there. In addition, since naturalists denounce every solid foundation, they must look for processes or properties that are reliable enough to fill in the role of a priori categories and principles (credibility for Kitcher, evolutionary theory for Rosenberg).

A controversy appears about the weight that the efforts for a scientific explanation should carry and the relative role of philosophy and science. We can thus distinguish naturalists to those who argue that epistemology should be completely replaced by science and those who argue that a part of the question remains that empirical research cannot access. This controversy already existed in Quine’s writings.

One can detect both a version of a “strong” naturalistic approach to epistemology, but also a “moderate” or “weak” approach (Haack, 1993; Stich, 1993). The first equates to scientism, the view that favours science as the best and therefore only method we should use to discover the world. The second sees science as complementary to philosophy and possibly as a source for its renewal.

As Haack (1993) points out, among others, this internal conflict in Quine’s writings arises in part from the different use of the term “science” (or “natural science”). We have already seen that Quine proposes that the work of epistemology be placed in the academic field of psychology –this is a view of the scientistic naturalism that Quine had in mind. But how can one think of the times when Quine considers philosophy and science to be part of the same continuum (see the parable of Neurath’s boat) or when he tells us that “science is self-conscious common sense” (Quine, 1960, p. 3)? At other times Quine includes economics, sociology, and history in the natural sciences (Hylton & Kemp, 2020; Sinclair, 2020) while denying, arbitrarily to many, the contribution of the study of the sociological and historical aspects of the issue to epistemology (Quine, 1969, p. 87).

Disagreements also arise over one’s position regarding the dilemma of realism versus anti-realism. In simple terms, this dilemma can be expressed as follows: is the image of the world that science offers us an accurate representation of the world itself or is it merely an instrumental conceptual form that we can use to access it? One would expect that the certainty required to promote the naturalistic approach as the prevailing epistemological approach would force any proponent to argue that scientific knowledge provide us an accurate depiction of reality. But the indeterminacy of translation seems to lead directly to anti-realism. Since two or more theories may equally well reflect the incoming empirical observations, which of the possible worlds they describe is real?

All these disagreements around the degree to which science should be involved in epistemology stem from the answers that naturalists attempt to provide to the two perceived deficiencies of naturalism –the argument from normativity and the argument from circularity– as well as from differing opinions on the degree of epistemology’s transformation after the emergence of naturalism. We will now examine whether a priori knowledge is supported assuming a naturalistic approach and the alternative sources of reliability that can emerge through scientific research.

The argument from circularity

The first flaw that can be directly identified in the naturalistic approach to epistemology is its circularity. The use of science in the attempt to explain the phenomenon of knowledge and science itself involves circularity: it appears to presuppose what is being attempted to explain. It is tantamount to question-begging and would be automatically considered condemnatory of any argument: the conclusion of the argument necessarily follows from one of the premises. To put it another way, how can one convince Descartes’ Skeptic that the world of our senses is true as we know it and we are not deceived? To achieve this (something that would give rise to the foundation of empirical science with complete certainty) this would have to be done outside the framework of science, which is itself based on experience.

An answer given to this argument by the supporters of the naturalistic approach, following Hume, is that in no way can we overcome our cognitive limitations. There is no way we can guarantee the certainty of our experience. As we have seen, Quine tells us that the problem no longer exists, as long as we stop dreaming of a logical reconstruction of science. The problem can be approached scientifically: “Subtracting his cues from his world view, we get man’s net contribution as the difference”. (Quine, 1960, p. 4). Of course, the findings of science will not have the certainty that Descartes was aiming for, but science can constantly self-correct.

In addition, according to Gödel’s theorems, a coherent formal system will either have unjustified initial assumptions or will be circular and feedback-based (Sosa, 1983). Proponents of the naturalistic approach will tend to prefer the latter. An approach attempting to base knowledge on logic –or any other property or process– would be equally doomed to circularity, as it would have to assume itself before trying to explain how it leads to knowledge.

Furthermore, a circular set of propositions whose circle is large enough, like a dictionary containing all the words of a language, does provide some information and cannot be considered a fallacy (Dowden, 2020). Something analogous in epistemology could be to form an as complete as possible dictionary of knowledge components. Logical Positivism proposed the language of formal logic (later supplemented by set theory); Quine proposed a change of language in favour of the language of science, or, in any case, the language closest to describing the world as it is. And it is to be expected that language will continue to evolve along the way. It is difficult to see how the whole of human knowledge can be judged as fallacious the same way as circular arguments.

Therefore, in relation to the issue of circularity, the two different approaches seem to be equivalent. In a rational reconstruction, assuming that one more successful than those already tested can exist, one or some of the cognitive or other qualities of man (or even human societies) will be considered the fundamental building blocks on which a theory of knowledge will based. On the other hand, according to the naturalistic approach, the equivalent to those foundations (the axioms of science) will be under constant review as new empirical data emerge. In the first case, the circle will be closed at the base of the hierarchy, close to the structural elements, which will be considered stable and any changes will be made to the elements closest to the periphery. In the second case, the structural elements can be constantly revised, as often as needed based on new findings.

The argument from normativity

The proponents of the naturalistic approach to epistemology have been accused of ignoring the normative aspect of epistemology. This aspect deals with the search for methods and values that should guide our decision making and our practice, and, in the context of epistemology, concerns the distinction between right and wrong theories and propositions. As Rosenberg puts it: “Ethics examines what we ought to do, epistemology what we ought to believe” (Rosenberg, 1999). Hume was the first to point out that empirical research findings cannot be applied indiscriminately. If we do not want to fall into the naturalistic fallacy, we must separate is from ought.

Kim (2008, pp. 540, 542) argues that Quine was the first to propose the removal of the concept of normativity from epistemology and its transformation from a project based on justification to an empirical quest now based on a descriptive science. This transition, Kim points out, also marks the expulsion of knowledge from epistemology (Kim, 2008, p. 542), a conclusion with which Quine himself would have little disagreement. Quine had renounced the concept of “knowledge” for serious use, along with that of “necessity”, “thought”, “belief”, “experience”, “meaning” and other terms that he considered vague, along with the philosophical questions that required their use because they had no clear boundaries (Hylton & Kemp, 2020; Sober, 2000). Stripped of justification and normativity, Quine’s undertaking bears no resemblance to epistemology, the way a traditional epistemologist understands it (Kim, 2008, p. 543).

The question that remains is this: if normativity is a necessary component of epistemology and any comprehensive candidate theory of human knowledge, where can it come from and how can it be justified to rigorously establish decisions and practice? The issue at this point intersects with the problems that arise in the philosophy of mind. How do people (or any other organism, society, or community) make decisions, and how do they distinguish right from wrong? We are bound to discuss these issues using the so-called intentional vocabulary, i.e. based on concepts such as beliefs, intentions, desires, etc. Therefore, if we want to establish the normativity of epistemology we must find a way to explain these concepts and how their meanings participate in the phenomena that interest us.

What is certain is that modern epistemology has moved away from trying to explain these phenomena in terms of formal logic like Logical Positivism attempted (Kitcher, 1992). If we choose the scientific approach, our theories will certainly be descriptive, at least in the early stages (Churchland, 1987). But if the intentional component of the mind can in principle be described by any scientific theory that will take on the task, we can assume that we will then be able to approach the question of which of the mediating processes are reliable and which are the ones that provide correct conclusions. And in this endeavour we can, possibly, find some support from evolutionary theory (Churchland, 1987; Kitcher, 1992; Quine, 1969; Rosenberg, 1999).

The human mind, insofar as it is a product of the human body, should be considered the result of biological evolution. This does not mean, of course, that the resulting picture will provide us with certainty against epistemological skepticism. However, it can place the processes that lead to knowledge in an evolutionary framework that will not isolate purely human properties from the rest of the phylogenetic scale while at the same time it will integrate them with the biological constraints (ecological, physical, genetic, etc.) that characterize the human species. We should, therefore, expect some degree of inherent uncertainty and error introduced through those processes. The identification of these weaknesses of the human mind is rather what leads those who support the naturalistic approach to resist an a priori consolidated depiction of human knowledge.

Critical analysis

The place of Quine’s work in modern epistemology

As we have already mentioned, Quine’s attempt was to salvage the legacy of Logical Positivism, transforming as many aspects of it as he considered problematic. The two main problems he focused on were the two doctrines of empiricism, as he called them, the doctrine of analyticity and the doctrine of reductionism. Instead, he proposes the psychological study of how members of the linguistic community become a part of it and how they interact, as replacements of analyticity and a priori knowledge in general, and the doctrine of holism, which in the context of scientific practice is implemented through the web of beliefs and leads to the indeterminacy of translation.

Quine’s contribution is now considered by most philosophers to have been instrumental in overthrowing the approach of Logical Positivism. The foundation of a priori knowledge in a linguistic approach as originally envisioned by Carnap could not succeed. Both Carnap himself in his latest writings and Quine showed that. However, contrary to Quine, not everyone agrees that the rejection of a foundation of knowledge in formal logic negates the possibility of a reconstruction based on any a priori conceptualization.

Some, therefore, disagree with Quine’s first dogma and the reduction of meaning to the stimulation of our sensory receptors (Friedman, 1997; Sober, 2000). Indeed, this approach carries the flaws of Quine’s behaviourism. Moreover, although Quine’s exposition convinces us that the concept of analyticity is vague no matter how it is defined, it is insufficient to convince us that there can only be one way to approach the issue (Sober, 2000).

The dogma of holism appears to be less questionable. It is generally accepted since Duhem’s time that no empirical observation can confirm a theoretical hypothesis (Losee, 2001, p. 150) as in most cases multiple auxiliary hypotheses are simultaneously tested together with some basic assumptions. It can be argued, however, that Quine’s epistemological holism does not follow from the premise. As the core assumptions, logic and mathematics are not tested in each experiment (Friedman, 1997; Sober, 2000). Even if Kant’s a priori framework, or any other intuition we may have does not apply, some preconditions of empirical science must always exist to serve as the constitutional function that Kant, at least according to one reading, had in mind (Friedman, 1997).

What is certain is that Quine’s work in epistemology sparked a great deal of debate about whether a naturalist epistemology is sound. We will now turn to evaluating some of the suggestions that have been raised.

Is a naturalistic epistemology possible?

Many philosophers followed Quine’s urge to include an empirical aspect in epistemology, even if they do not fully agree with his analysis. As we have seen, the contribution of evolutionary theory to this endeavour is considered by many to be promising. We have to note here, in concert with Kitcher (Kitcher, 1992, p. 91, footnote 97) that evolutionary thought can contribute to epistemology in two ways: either as a theoretical framework that offers the required credibility to the processes under question, or to give us the theoretical model, analogously to biological evolution, through which a theory of knowledge can be developed in formal terms.

Rosenberg believes that a naturalistic epistemology is bound to apply evolutionary thought to explain the phenomenon of knowledge (Rosenberg, 1999). For him, the result is a re-structuring of the debate and moving it away from a search for truth –focusing on truth does not necessarily ensure survival. On the other hand, framing the issue in terms of fitness and reproductive success alone is not capable to illuminate all the processes involved in the phenomenon. We can imagine conditions of evolutionary pressure in which mental wealth arose accidentally or indirectly, due to its relevance to other traits that provided an evolutionary advantage. In particular, the mental framework that supports knowledge could be an epiphenomenon, i.e. a result of random drift and other non-selective forces that evolutionary theory has identified. However, it is reasonable to think that traits such as “logic”, which appear to play an important role in human ecology have been favourably selected during our long evolution.

Nevertheless, evolutionary theory can only provide the general theoretical background for articulating a comprehensive theory of knowledge in the context of a naturalistic approach to epistemology. A substantial part of the scientific burden should be borne by psychology and related fields. Only through studies at this level can we identify the possible functions for which our mental capabilities are destined. Only after these functions are identified will we be able to produce a comprehensive theory of human knowledge that respects our phylogenetic course, the ecology of our species during its evolution, its ontogenetic and developmental limitations, and the extent of the diversity of relevant traits. At that point we will have reconstructed nature’s mental vocabulary and we will be then able to reconstruct scientific practice itself.

However, it should be noted that such an endeavour must simultaneously spread across multiple levels of description, unlike the opportunistic way science has moved so far (Lewontin, 2001, p. 72).

At one level, for example, Stich (Stich, 1993) notes that considerable differences between individuals are expected to be found in the way that they manage available knowledge and scientific evidence to form a scientific theory and this heterogeneity will vary with factors such as education and other cultural characteristics. He, therefore, suggests that epistemology should be interested in studying not how each subject manages knowledge but rather how scientists who are most efficient at it, do it. Even if Stich’s suggestion needs further support, as he does not define how a method’s effectiveness will be judged, his observation that individual differences have been so far ignored is constructive. In fact, Stich is one of the few philosophers who fully embraced Quine’s urge and actively collect data to feed their philosophical analyses, e.g. (Nichols et al., 2003).

Another aspect that needs to be studied is the social dimension of knowledge. Issues that Kitcher (Kitcher, 1992) identifies at this level are the dissemination of knowledge through the existing web, the distinction between personal and impersonal scientific goals, the management of scientific disputes, and the recognition that subjects of knowledge may also have non-epistemic goals. He considers these issues the subject of the field of social epistemology. Issues such as the role of authority in science and communication between proponents of opposing theories posed by Kuhn (Kuhn, 1996) can in this context be accessed through empirical science.

In an even greater context, naturalistic epistemology could study the goals of science over time. Given that it is expected that those goals cannot remain constant but change, empirical research may identify the criteria by which they change. Whether one of those is realizability, which Laudan rather reasonably concludes, or some other goal, it remains to be determined through empirical research (Freedman, 2006).

The above discussion demonstrates that a new meta-epistemological movement is starting to develop inside modern epistemology, which aims to study the whole spectrum of phenomena related to human knowledge. The integration of all those perspectives in a unified theoretical approach promises to provide a holistic description of the processes involved in all related levels and their interactions.

Given that such a theoretical framework will have emerged through empirical study, we should expect a certain degree of epistemological relativism. Nevertheless, we will have reached a level of description that encompasses all human activity related to the phenomena of knowledge and science. The freedom of choosing between multiple potential alternatives ways to approach phenomena related to knowledge can only be regarded as an advantage. Since it is proven that any rational reconstruction of knowledge will necessarily be impossible or incoherent, any limits or constraints on our perception of the world and our actions are bound to be arbitrary if they are not based on empirical research.

Although such a presentation is not the subject of this work, efforts to articulate such integrated theories exist. One such example is Damasio’s theory of embodied cognition, specifically its account for the emergence of consciousness (Antonio R Damasio, 2000). In addition, philosophical conceptualization is progressively applied in the field of Neuroscience, as much of the discussion revolves around how biological systems can learn their environment through prediction and control (Friston, 2010), which philosophers set as the goals of knowledge (Kitcher, 1992; Rosenberg, 1999).

Summary

As it has become apparent so far, Quine generated a wave of discussion throughout the second half of the 20*t*h century regarding the foundations of epistemology. His main contribution was to identify the impasses of Logical Positivism. We must emphasize that his criticism focused on distinguishing between analytic and synthetic propositions. Therefore his analysis cannot be considered condemning for any a priori epistemology. Furthermore, Quine does not provide a convincing reason to believe that “humans, branches, rocks, electrons, and molecules are indeed real” (Sosa, 1983, p. 68). Essentially, he does not state how naturalism is legitimized to claim that it delivers us the world, if it cannot show that its theoretical objects are indeed part of nature. Another severe limitation is the arbitrary way in which he suggests who is entitled to practice naturalistic epistemology: why not Kuhn or Piaget and even Chomsky with his universal grammar, which is clearly against expunging the idea of a a priori. Finally, his psychological approach to meaning and knowledge is purely behaviouristic, and carries the weaknesses of that approach.

As we have noted before, one element that may be useful in the future is the recognition of the non-scientific aspects of knowledge, which the unbridled scientism of Quine and some proponents of the naturalistic approach strikingly ignore. Ultimately, what is missing from modern epistemology is a general framework that integrates all the knowledge that the natural sciences produce. The intersection needed is to construct a unified view of the cognitive and biological frames of reference, together with the corresponding social and historical ones in a perspective of human goals, transcending all levels of complexity of the relevant phenomena. We have already stressed how important it is to integrate this project into a more general evolutionary context at both the ontogenetic and phylogenetic levels.

Taking on the task exemplifies the clash between two entire traditions of explanatory models: the so-called causal-mechanistic and the holistic (Salmon et al., 1992, pp. 33–34). In most cases, empirical science tends to turn to the tradition of causal models. But this view stems, I believe, from a short-sighted view of the historiography of scientific practice. Although these models appear to be the most widespread in scientific methodology, scientists often resort to more holistic explanations, especially in times of crisis. I believe that the present situation, with the attack of the natural sciences on questions about the nature of mental phenomena, is one of them.

We can argue that, to some extent, this struggle between the two approaches, which very often coexist even in the same person, reflects the more general relationship between philosophy and science. Necessarily, rather, philosophy is oriented towards a more holistic approach, while science towards the causal explanation of the phenomena around us. To the extent that they both aim to make us more aware of the world –including ourselves– their action should be complementary. At stake in the Carnap-Quine controversy and the ensuing debate is whether we should assign distinct roles to philosophy and science. It seems, at first, that each has a distinct role, as philosophy deals with conceptual analysis while science with the collection of empirical data. But empirical science can not be carried out without philosophical thought, and philosophy would be useless if it were developed to deal with all possible worlds. Newton’s motivation to oppose Descartes’s metaphysical natural science (Losee, 2001, p. 93) and the subsequent influence of Newton’s work on Kant’s thought, as we have seen, most clearly demonstrate this productive interaction.

If we want to tackle the question of the possibility of a priori knowledge (and on any other issue, as far as I can see), we must, at least first, use some conceptualization. It is only through an existing conceptualization that we can discuss any issue in the first place. The development of centuries of philosophy offers us such a conceptualization.

But it is to be expected –and human– that any conceptualization can be wrong. For example, although centuries of empirical research have confirmed the existence of an innate conception of space presupposed by Kant (Moser et al., 2008; Palmer & Lynch, 2010), it seems that it has defining properties that could not be accessible at the time Kant wrote (Wills et al., 2010). More recently, Putnam (Putnam, 1982) argues that force fields, brown objects, and dispositions are three non-reducing things or properties. Today we know that he is wrong on brown objects, we have some theoretical models of how to describe fields in more simple terms (Witten, 2005) and some indications that something similar could be true of the dispositional component of the mind. So I would say that we are obliged to use the best conceptualization that philosophy and philosophical thought, in general, offer us each time. However, if we want to make existing conceptualizations clearer and thus of more use, we must put it to every available test. The scientific methodology is, to date, the best process we have to test compatibility with the real world. Our best knowledge will always be after the fact. Concepts and explanations will be mutually reshaped through their interaction.

After all, does science give us a realistic view of the world? The proponent of the naturalistic approach will ask: in relation to which reality? The theory of evolution suggests that there are almost as many ways of seeing (sic) the world as there are different species, and the cognitive sciences that considerable diversity may exist even among individuals of the same species. For our species, the part of common sense that has developed to the point that it has acquired self-awareness, as Quine describes science, is that which appears to display the most potential for describing to us the world. We must use its findings with due respect for its limitations and specifications, at the cost of continually reviewing its results and by taking all the other virtues that make science possible as given.

The relativism stemming from a scientific inquiry of epistemology’s foundations should not frighten us. The diversity of the subjects’ traits, their societies and their history should be taken for granted and should not be obscured. Only through deliberate study along the lines we have outlined can a continued reconstruction of the related phenomena’s useful features be produced. Such an empirical reconstruction will help us become more and more aware of our structural relations with the world and the ways in which we interact. Our species stands out through our ability to reflect on our own history over long periods of time, both individually and collectively. We must pursue opportunities for reflection by every means at the disposal of the human mind. Although all this may sound idealized, we can not afford to leave it to chance. A well-defined dividing line between philosophy and science is of no use –only the synthetic adoption of their guidelines by each individual can help us move forward.

I want to pause and meditate for a while on this new knowledge of mine, fixing it more deeply in my memory.

(Descartes, 1614, Second Meditation, p. 8)

I am afraid that my peaceful sleep may be followed by hard labour when I wake, and that I shall have to struggle not in the light but in the imprisoning darkness of the problems I have raised.

(Descartes, 1614, First Meditation, p. 3)

References

Antonio R Damasio. (2000). The feeling of what happens. Harcourt Inc. http://archive.org/details/feelingofwhathap00dama_0

Carnap, R. (1950). Empiricism, Semantics, and Ontology. Revue Internationale de Philosophie 4, 20–40.

Churchland, P. S. (1987). Epistemology in the Age of Neuroscience. In The Journal of Philosophy (No. 10; Vol. 84, pp. 544–553). https://www.pdcnet.org/pdc/bvdb.nsf/purchase?openform&fp=jphil&id=jphil_1987_0084_0010_0544_0553. https://doi.org/10.5840/jphil1987841026

Descartes, R. (1614). Meditations on First Philosophy in which are demonstrated the existence of God and the distinction between the human soul and body (J. Bennett, Trans.).

Dowden, B. (2020). Fallacies. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Fieser, J. (2011). Hume: Metaphysical and Epistemological Theories. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Freedman, K. L. (2006). Normative Naturalism and Epistemic Relativism. International Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 20(3), 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/02698590600960952

Friedman, M. (1997). Philosophical Naturalism. Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association, 71(2), 5+7–21. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3130938

Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: A unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2787

Haack, S. (1993). The two faces of Quine’s naturalism. Synthese, 94(3), 335–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01064484

Hylton, P., & Kemp, G. (2020). Willard Van Orman Quine. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2020). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Kim, J. (2008). What Is “Naturalized Epistemology”? In Epistemology: An Anthology. John Wiley & Sons.

Kitcher, P. (1992). The Naturalists Return. The Philosophical Review, 101(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.2307/2185044

Kuhn, T. S. (1996). The structure of scientific revolutions (3rd ed). University of Chicago Press.

Lewontin, R. C. (2001). The Triple Helix: Gene, Organism, and Environment. Harvard University Press. https://books.google.com?id=otKbHE8OFy4C

Losee, J. (2001). A Historical Introduction to the Philosophy of Science (Fourth Edition). Oxford University Press.

McCormick, M. (2020). Immanuel Kant: metaphysics. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Moser, E. I., Kropff, E., & Moser, M.-B. (2008). Place Cells, Grid Cells, and the Brain’s Spatial Representation System. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 31(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.061307.090723

Nichols, S., Stich, S., & Weinberg, J. M. (2003). Metaskepticism: Meditations in Ethnoepistemology. In S. Luper (Ed.), The Skeptics (pp. 227–247). Ashgate.

Palmer, L., & Lynch, G. (2010). A Kantian View of Space. Science, 328(5985), 1487–1488. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1191527

Papineau, D. (2020). Naturalism. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2020). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Putnam, H. (1982). Why Reason Can’t Be Naturalized. Synthese, 52(1), 3–23. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20115757

Quine, W. V. (1951). Two Dogmas of Empiricism. The Philosophical Review, 60(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.2307/2181906

Quine, W. V. (1960). Word and object (New edition). MIT Press.

Quine, W. V. (1969). Epistemology Naturalized. In Ontological Relativity and Other Essays. New York: Columbia University Press.

Rosenberg, A. (1996). A Field Guide to Recent Species of Naturalism. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 47(1), 1–29.

Rosenberg, A. (1999). Naturalistic Epistemology for Eliminative Materialists. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 59(2), 335–358. https://doi.org/10.2307/2653675

Salmon, M. H., Earman, J., Lennox, J. G., Machamer, P., Glymour, C. N., Salmon, W. C., McGuire, J. E., Norton, J. D., & Schqffner, K. F. (Eds.). (1992). Introduction to the Philosophy of Science. Prentice Hall.

Sinclair, R. (2020). Willard Van Orman Quine: Philosophy of Science. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Sober, E. (2000). Quine: Elliott Sober. Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume, 74(1), 237–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8349.00071

Sosa, E. (1983). Nature unmirrored, epistemology naturalized. Synthese, 55(1), 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00485373

Stich, S. (1993). Naturalizing Epistemology: Quine, Simon and the Prospects for Pragmatism. Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement, 34, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1358246100002435

Stroud, B. (1996). The Charm of Naturalism. Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association, 70(2), 43. https://doi.org/10.2307/3131038

Wills, T. J., Cacucci, F., Burgess, N., & O’Keefe, J. (2010). Development of the Hippocampal Cognitive Map in Preweanling Rats. Science, 328(5985), 1573–1576. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1188224

Witten, E. (2005). Unravelling string theory. Nature, 438(7071, 7071), 1085–1085. https://doi.org/10.1038/4381085a