Git is a source control tool developed

for the needs of the Linux kernel project.

Many software projects are now using the Git protocol

as is evident by the popularity of services such as GitHub, GitLab and BitBucket

that rely on Git.

But its usefulness extends far beyond managing computer code.

Through this collection of memes article,

I will introduce the basics of using Git,

focusing on how it can be useful for academic research.

But first some motivation on why a better tool

for scientific collaboration is needed.

If you are rather convinced that this is the case,

feel free to skip the motivation section

and move directly to the section describing

basic Git usage.

Table of Contents

Motivation

Scientific practice needs to

- be collaborative

- be documented

- be open

- be amenable to revision

- include verifiable computer code

Scientists need to collaborate in a way that gracefully and robustly handles concurrent editing. Common practices to handle even simple cases of single-file versioning edited by few collaborators are cumbersome. An example that should be familiar to all academic researchers is to have a folder piled with versions of a single document like this:

final.doc

final_v1.doc

final_v1_VK.doc

final_v1_VK_XY.doc

final_v2.doc

...

final_v99.doc

final_for_real.doc

‘Piled Higher and Deeper’ by Jorge Cham, www.phdcomics.com

You can, of course, use the “track changes” feature in a text editor such as Microsoft Word or LibreOffice, but that results in unnecessary file duplication like the one shown above and is not manageable once the project involves more than one author. This method can be very slow as you would need to wait for all authors to send their version to someone whose version serves as the master who then must re-send the merged version to the rest of collaborators. The purpose of distributed source control systems, such as Git, is to enable multiple people to work on the same project in parallel or asynchronously. In combination with using a central online repository, everyone can have immediate access to the latest master version, while at the same time working on their private copies.

In addition to the file versioning problem discussed above, computer code for scientific research is often filled with comments like this:

# do_thing0

do_thing1

# do_thing2 # Was useful when I used to do_thing0 instead of do_thing1

Putting your code under version control with a tool such as Git allows you to restore previous versions of your code with little effort.

Another example where traditional methods of ad-hoc version control are inadequate is multi-file versioning, such as when some piece of code, documentation, the associated raw data, and the produced images all change together. When you place reproducible documents, such as Rmarkdown or Jupyter notebooks, under version control with a tool such as Git, you can handle any changes to some of the pieces of a project in one step.

What happens if you edit a paragraph of your precious manuscript or code only to realize that a previous version was better? Sure, syncing services such as Dropbox have saved the day for me in some instances with their version history feature, but I have had to re-write parts of a piece of text or code almost equally often in cases where the version I was looking for was older than the versions kept in history. Git offers ease of mind regarding data loss, though without removing the need for backups, as it makes it very difficult for someone to lose data by accident. As long as you regularly commit your changes, you need advanced skills to re-write Git history.

Collaborating on a single document stored in a syncing service such as Dropbox is asking for trouble, as even with two collaborators file conflicts are to be expected. Simultaneously editing a file in Google Docs, although admirably powerful, can be very distractive as a change introduced by someone may disrupt another person’s work. But with Git every collaborator is working with a private copy, or branch as we will later see. Changes inside a private branch do not affect other branches. Git includes tools for merging divergent branches and a streamlined conflict resolution method for the unavoidable merge conflicts.

What Git offers

At the most basic level, Git automatically tracks the answers to the questions:

- What has changed?

- Who made the change?

- When was the change made?

and in addition motivates you to answer the question

- Why did it change/ What is this change about?

when you commit a change.

When you use Git as a researcher, you get a free, feature-full, shareable notebook for text-based work.

A side-effect of using Git is that I feel more productive, as I can keep track of my work in chunk-sized achievements when browsing my projects’ Git log.

Basic command line usage

People often describe Git as a cryptic and complicated tool:

Heeding some of your suggestions about version control issues, I've just tried installing git.

— Lego Grad Student (@legogradstudent) March 30, 2018

I can't help but feel that it is designed to be borderline inaccessible so that people who do use it can be smug.

Such complaints are not without reason. Just look at the list of all possible commands (excluding subcommands):

git help -a

## See 'git help <command>' to read about a specific subcommand

##

## Main Porcelain Commands

## add Add file contents to the index

## am Apply a series of patches from a mailbox

## archive Create an archive of files from a named tree

## bisect Use binary search to find the commit that introduced a bug

## branch List, create, or delete branches

## bundle Move objects and refs by archive

## checkout Switch branches or restore working tree files

## cherry-pick Apply the changes introduced by some existing commits

## citool Graphical alternative to git-commit

## clean Remove untracked files from the working tree

## clone Clone a repository into a new directory

## commit Record changes to the repository

## describe Give an object a human readable name based on an available ref

## diff Show changes between commits, commit and working tree, etc

## fetch Download objects and refs from another repository

## format-patch Prepare patches for e-mail submission

## gc Cleanup unnecessary files and optimize the local repository

## gitk The Git repository browser

## grep Print lines matching a pattern

## gui A portable graphical interface to Git

## init Create an empty Git repository or reinitialize an existing one

## log Show commit logs

## maintenance Run tasks to optimize Git repository data

## merge Join two or more development histories together

## mv Move or rename a file, a directory, or a symlink

## notes Add or inspect object notes

## pull Fetch from and integrate with another repository or a local branch

## push Update remote refs along with associated objects

## range-diff Compare two commit ranges (e.g. two versions of a branch)

## rebase Reapply commits on top of another base tip

## reset Reset current HEAD to the specified state

## restore Restore working tree files

## revert Revert some existing commits

## rm Remove files from the working tree and from the index

## shortlog Summarize 'git log' output

## show Show various types of objects

## sparse-checkout Initialize and modify the sparse-checkout

## stash Stash the changes in a dirty working directory away

## status Show the working tree status

## submodule Initialize, update or inspect submodules

## switch Switch branches

## tag Create, list, delete or verify a tag object signed with GPG

## worktree Manage multiple working trees

##

## Ancillary Commands / Manipulators

## config Get and set repository or global options

## fast-export Git data exporter

## fast-import Backend for fast Git data importers

## filter-branch Rewrite branches

## mergetool Run merge conflict resolution tools to resolve merge conflicts

## pack-refs Pack heads and tags for efficient repository access

## prune Prune all unreachable objects from the object database

## reflog Manage reflog information

## remote Manage set of tracked repositories

## repack Pack unpacked objects in a repository

## replace Create, list, delete refs to replace objects

##

## Ancillary Commands / Interrogators

## annotate Annotate file lines with commit information

## blame Show what revision and author last modified each line of a file

## bugreport Collect information for user to file a bug report

## count-objects Count unpacked number of objects and their disk consumption

## difftool Show changes using common diff tools

## fsck Verifies the connectivity and validity of the objects in the database

## gitweb Git web interface (web frontend to Git repositories)

## help Display help information about Git

## instaweb Instantly browse your working repository in gitweb

## merge-tree Show three-way merge without touching index

## rerere Reuse recorded resolution of conflicted merges

## show-branch Show branches and their commits

## verify-commit Check the GPG signature of commits

## verify-tag Check the GPG signature of tags

## whatchanged Show logs with difference each commit introduces

##

## Interacting with Others

## archimport Import a GNU Arch repository into Git

## cvsexportcommit Export a single commit to a CVS checkout

## cvsimport Salvage your data out of another SCM people love to hate

## cvsserver A CVS server emulator for Git

## imap-send Send a collection of patches from stdin to an IMAP folder

## p4 Import from and submit to Perforce repositories

## quiltimport Applies a quilt patchset onto the current branch

## request-pull Generates a summary of pending changes

## send-email Send a collection of patches as emails

## svn Bidirectional operation between a Subversion repository and Git

##

## Low-level Commands / Manipulators

## apply Apply a patch to files and/or to the index

## checkout-index Copy files from the index to the working tree

## commit-graph Write and verify Git commit-graph files

## commit-tree Create a new commit object

## hash-object Compute object ID and optionally creates a blob from a file

## index-pack Build pack index file for an existing packed archive

## merge-file Run a three-way file merge

## merge-index Run a merge for files needing merging

## mktag Creates a tag object with extra validation

## mktree Build a tree-object from ls-tree formatted text

## multi-pack-index Write and verify multi-pack-indexes

## pack-objects Create a packed archive of objects

## prune-packed Remove extra objects that are already in pack files

## read-tree Reads tree information into the index

## symbolic-ref Read, modify and delete symbolic refs

## unpack-objects Unpack objects from a packed archive

## update-index Register file contents in the working tree to the index

## update-ref Update the object name stored in a ref safely

## write-tree Create a tree object from the current index

##

## Low-level Commands / Interrogators

## cat-file Provide content or type and size information for repository objects

## cherry Find commits yet to be applied to upstream

## diff-files Compares files in the working tree and the index

## diff-index Compare a tree to the working tree or index

## diff-tree Compares the content and mode of blobs found via two tree objects

## for-each-ref Output information on each ref

## for-each-repo Run a Git command on a list of repositories

## get-tar-commit-id Extract commit ID from an archive created using git-archive

## ls-files Show information about files in the index and the working tree

## ls-remote List references in a remote repository

## ls-tree List the contents of a tree object

## merge-base Find as good common ancestors as possible for a merge

## name-rev Find symbolic names for given revs

## pack-redundant Find redundant pack files

## rev-list Lists commit objects in reverse chronological order

## rev-parse Pick out and massage parameters

## show-index Show packed archive index

## show-ref List references in a local repository

## unpack-file Creates a temporary file with a blob's contents

## var Show a Git logical variable

## verify-pack Validate packed Git archive files

##

## Low-level Commands / Syncing Repositories

## daemon A really simple server for Git repositories

## fetch-pack Receive missing objects from another repository

## http-backend Server side implementation of Git over HTTP

## send-pack Push objects over Git protocol to another repository

## update-server-info Update auxiliary info file to help dumb servers

##

## Low-level Commands / Internal Helpers

## check-attr Display gitattributes information

## check-ignore Debug gitignore / exclude files

## check-mailmap Show canonical names and email addresses of contacts

## check-ref-format Ensures that a reference name is well formed

## column Display data in columns

## credential Retrieve and store user credentials

## credential-cache Helper to temporarily store passwords in memory

## credential-store Helper to store credentials on disk

## fmt-merge-msg Produce a merge commit message

## interpret-trailers Add or parse structured information in commit messages

## mailinfo Extracts patch and authorship from a single e-mail message

## mailsplit Simple UNIX mbox splitter program

## merge-one-file The standard helper program to use with git-merge-index

## patch-id Compute unique ID for a patch

## sh-i18n Git's i18n setup code for shell scripts

## sh-setup Common Git shell script setup code

## stripspace Remove unnecessary whitespace

##

## External commands

## shell

What could merge-octopus possibly mean?

I freely admit that I did not know what this command was for

before writing this post,

and I still do not know what many of the other commands do.

Luckily, you only need a few commands to get by for basic use.

xkcd.com

I will first describe some basic commands for use through a terminal. However, many text editors or IDE’s now offer a way to use these basic commands through a guided user interface. For more advanced usage, there are even standalone graphical git clients and we will see some examples of graphical interfaces for Git later in this post.

To install Git, if it is not already installed in your system,

follow the instructions in this link:

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Getting-Started-Installing-Git.

The first thing you need to do next is to go to a terminal (or command window in Windows) and enter the following lines, replacing the placeholder text with your full name and email address, to introduce yourself to Git:

git config --global user.name "Full Name"

git config --global user.email "demo@email.com"

Optionally, you can also set the default text editor to your favourite one. I use the terminal-based nano

git config --global core.editor "nano -w"

but you could also use a graphical editor such as Atom

git config --global core.editor "atom --wait"

You can find a list of configuration commands for some popular editors with a graphical user interface in https://swcarpentry.github.io/git-novice/02-setup/.

You only need to set these options once in every computer and they will be valid for all your repositories.

Git repositories are folders that you have instructed Git to track. You can achieve this for a folder like so:

mkdir git-demo # Create folder

cd git-demo # Move to that folder

git init # Tell Git to start watching this folder

## hint: Using 'master' as the name for the initial branch. This default branch name

## hint: is subject to change. To configure the initial branch name to use in all

## hint: of your new repositories, which will suppress this warning, call:

## hint:

## hint: git config --global init.defaultBranch <name>

## hint:

## hint: Names commonly chosen instead of 'master' are 'main', 'trunk' and

## hint: 'development'. The just-created branch can be renamed via this command:

## hint:

## hint: git branch -m <name>

## Initialized empty Git repository in /builds/neurathsboat.blog/posts/git-intro/git-intro/src/git-demo/.git/

Git has created a hidden folder called .git inside git-demo

in which it will store all the files it needs to keep track of the repository.

ls -la

## total 12

## drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 4096 Jun 3 12:17 .

## drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 4096 Jun 3 12:17 ..

## drwxr-xr-x 7 root root 4096 Jun 3 12:17 .git

If you ever delete this hidden folder all info Git had on your repository will be gone. To check the status of our repository we can run the following line:

git status

## On branch master

##

## No commits yet

##

## nothing to commit (create/copy files and use "git add" to track)

By default, Git creates a branch called master in which it will hold

all future changes unless told otherwise.

A branch is a collection of commits.

A commit is simply a snapshot of the repository’s history.

Currently, there are no commits to show

–let’s create one.

To do that, first I need to create a new file, called test.txt,

and write something in it.

I will only write the word “spam”.

touch test.txt # Create file

echo spam >> test.txt # Write "spam" inside test.txt

cat test.txt # Display file contents

## spam

Now Git reports that it found the new file:

git status

## On branch master

##

## No commits yet

##

## Untracked files:

## (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

## test.txt

##

## nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

You can create or edit files

in a git repository as you normally would,

for example through a graphical text editor.

You can continue adding or editing files,

until you feel you need to keep

the repository’s contents in Git history.

There are typically two steps to follow.

First, you need to stage the changes,

which provides a way to select

which of all the available changes

to the files or portions of files you have made

are to be kept in Git history.

git add test.txt

git status

## On branch master

##

## No commits yet

##

## Changes to be committed:

## (use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

## new file: test.txt

Once we are happy with our changes, we need to tell Git to record this version in its history for good:

git commit -m "Include spam"

## [master (root-commit) e68d4fd] Include spam

## 1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

## create mode 100644 test.txt

By using the -m flag,

which stands for “message”,

we are permanently attaching

the description that follows it

to the changes made.

Using this command, Git will commit the staged changes

but not any changes you made to the staged files

after you staged them.

git log --graph --pretty=format:'%h <%an> %s%d'

# Show a graph log with the short commit hash, the author, the commit message and the commit reference

## * e68d4fd <Vassilis Kehayas> Include spam (HEAD -> master)

There is an art to writing descriptive yet concise Git commit messages. One guiding principle could be to write in the imperative present tense (e.g. “Fix indentation in preprocessing block”), as if trying to complete the sentence “If applied, this commit will …”. For more on the subject of commit messages, see https://chris.beams.io/posts/git-commit/.

xkcd.com

Now suppose that your text or code becomes complex enough that you may need to edit different parts of the file or multiple files at the same time. This may also be the case if a collaborator wants to edit the same files as you. But you still want to have a master version (branch) of your project that contains the last state of the project that is known to work or that everyone has provisionally accepted. The way to achieve this with Git is to create a separate branch that will contain the new versions of the files you wish to edit.

git checkout -b develop

## Switched to a new branch 'develop'

With the above command, I created a new branch called develop

and switched to it.

As it stands, it is in exactly the same state as the master branch.

But now any file edits will not propagate to the master branch,

unless you want to.

echo "I am developing" >> test.txt

cat test.txt

## spam

## I am developing

Calling git status now shows that our file is modified

compared to the previous state:

git status

## On branch develop

## Changes not staged for commit:

## (use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

## (use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

## modified: test.txt

##

## no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

We can issue git diff to observe the changes:

git diff test.txt

## diff --git a/test.txt b/test.txt

## index 34b6a0c..8c5bb19 100644

## --- a/test.txt

## +++ b/test.txt

## @@ -1 +1,2 @@

## spam

## +I am developing

The output shows us that Git has detected the inserted new line of text.

We can preserve our edits by staging and committing the file changes,

this time in one step by additionally using

the -a flag, which stands for add,

together with the -m flag for git commit we used before:

git commit -am "Include asinine statement"

## [develop 5fc1c88] Include asinine statement

## 1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

If for some reason we change our minds and decide to revert the file to the state it was before our latest commit we can use

git checkout HEAD~1 test.txt

cat test.txt

## Updated 1 path from 8cc4a03

## spam

which instructs Git to revert the file test.txt to the state it was

one commit before the latest (the HEAD).

To revert a file to a specific time in history

we first list the different commits

git log --graph --pretty=format:'%h <%an> %s%d'

## * 5fc1c88 <Vassilis Kehayas> Include asinine statement (HEAD -> develop)

## * e68d4fd <Vassilis Kehayas> Include spam (master)

and then checkout the commit that corresponds

to the version we are looking for:

git checkout e68d4fd test.txt.

To revert more than one files at the same time

some care should be taken to avoid the

dreaded “detached head” state.

To revert back to the latest state of the file Git has recorded

we simply checkout the branch’s HEAD

git checkout HEAD test.txt

## Updated 1 path from 12ab01c

At some point, we will feel that our edits are complete.

We can then merge the changes we made in the develop branch

with the master branch.

First, we need to switch back to the master branch

and then use the git command merge:

git checkout master

git merge develop

## Switched to branch 'master'

## Updating e68d4fd..5fc1c88

## Fast-forward

## test.txt | 1 +

## 1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

git log --graph --pretty=format:'%h <%an> %s%d'

## * 5fc1c88 <Vassilis Kehayas> Include asinine statement (HEAD -> master, develop)

## * e68d4fd <Vassilis Kehayas> Include spam

Here we merged a local branch to another local branch stored in the same machine. But say you want to send your changes to a collaborator. There are many ways to do this, for example by emailing a patch that contains the differences between your edits and the master version, or directly through Git itself. However, it is more convenient if there is an authoritative version that everyone can easily access.

Remote git repositories

This is where online services such as GitHub and GitLab come in. Both GitHub and GitLab offer free public repositories with many useful features. Although GitHub is by far the most popular such service, I prefer GitLab as it is open source which means that, among other benefits, it can be self-hosted if need-be, it offers unlimited private repositories without restrictions on the number of collaborators, and it is more focused on providing a complete toolchain for project development out of the box. However, the basic setup I will describe next is exactly the same for either remote service.

While anyone can view public GitLab projects, you need to create an account to create or interact with a hosted project. Interacting with your GitLab repository outside its own web interface will be simplified if you create an SSH key pair, if you do not already have one:

ssh-keygen -o -t rsa -b 4096 -C "demo@email.com"

and associate the public key with your GitLab account.

You will encounter the following screen when navigating to the project creation page:

After creating your project, GitLab conveniently lists the commands you need to run to sync your repository with their servers:

In our case, we already have a local Git project set up so we just need to link it to the GitLab project. To achieve this, we need to add the GitLab project as a remote repository to our local repository and push the changes:

git remote add origin git@gitlab.com:neurathsboat/git-demo.git

git push -u origin --all

git push -u origin --tags

Next time we make some changes that we need to sync with GitLab, we only need to run the following command after our commit:

git push origin master

or simply

git push

that uses origin as the default remote and master as the default branch.

When we want to make sure that we are working with

the most current version of a repository we need to pull from GitLab:

git pull

and continue working as described above.

Now that we have a shared remote repository, when we want to merge a local branch with the master branch of the remote repository we can open a merge request (or pull request in GitHub’s terminology). The main difference with a local merge as the one we performed before is that now collaborators of a project are free to submit a new merge request, or to review an existing merge request and suggest improvements or comments on the merge request as a whole:

or for particular pieces of it:

Some other benefits of using a service such as GitLab that we will not expand on more in this post are issues and Kanban boards, that it provides an extra place to backup your code, text, and small data, and continuous integration/continuous development.

Guided user interfaces

Despite the flexibility it offers, using the command line is a deterrent for some people. However, everything that we have done so far with Git and even more can be performed from inside the comfort of a modern text editor, IDE (not you, MATLAB), or dedicated software application.

Here is a screenshot of the Git panel inside the Atom text editor:

in Rstudio:

and GitKraken:

A more detailed description of Git plumbing

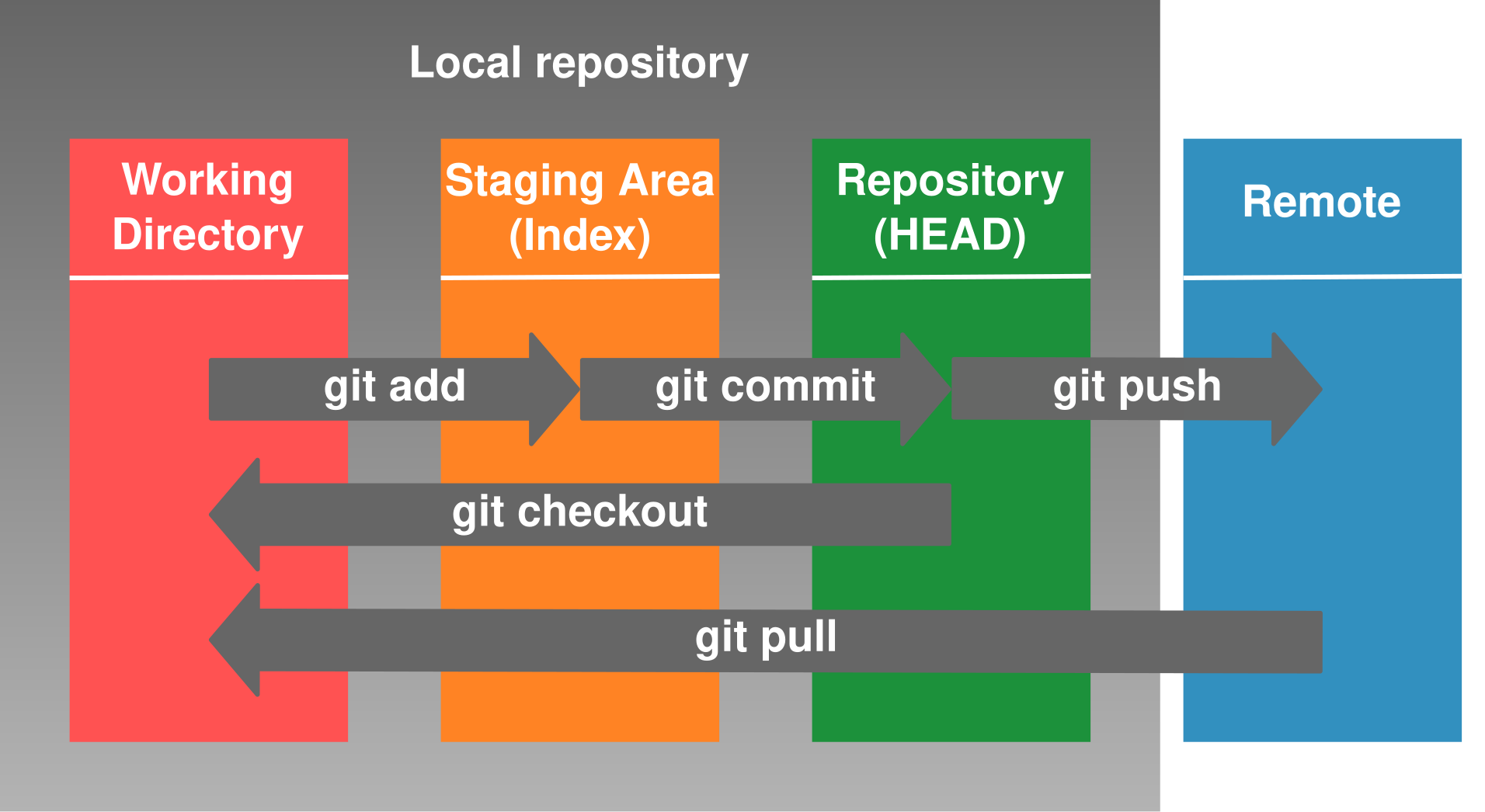

For anyone who wishes to go slightly deeper into the workings of Git here is a summary of the operations we have used in this tutorial, described in more detail.

We can describe a Git repository as

an array of sequentially connected objects

that each stores different kinds of information

about the state of a project.

The working directory represents the state of the local filesystem.

Git internally uses a database of files named through a

hash function,

called blobs,

that contain the content of the tracked files in your filesystem

for a given Git repository.

The staging area, or Index, corresponds to a special Git object, called

a Git tree,

that collects states of the files you have specified through git add.

To permanently store the contents of your staged files in the Git repository,

you run git commit,

which creates a commit object that updates the staging area

and references the trees and the commits that came before it.

Since each recorded state of a repository can be referenced by a commit hash,

any such state can be reinstated by git checkout.

By default, Git creates a master branch

that automatically tracks the latest commit or HEAD.

But you can make the HEAD track another branch or commit

that deviates from master

by using git checkout some-pre-existing-branch-name

or git checkout -b branch-that-will-be-created.

Later, you can switch back to the master (or any other branch)

by using git checkout master which will again point the HEAD

to the last known state of the master branch.

When you merge branch B into branch A with

git checkout A

git merge B

you are specifying that you wish for the history of branch B

to be a part of branch A.

For an interactive version of the above schematic

which also includes commands that we have not covered in this post see

http://ndpsoftware.com/git-cheatsheet.html.

A remote repository is just another Git repository

(technically a bare repository,

i.e. one without a working directory

since no one is directly writing to its filesystem).

To include in your local repository any newer changes

that a remote repository contains,

you need to git fetch to download the data

and then git merge to merge them to your local state,

or use git pull to perform both operations at once.

The reverse operation,

i.e. publishing your local state to a remote repository,

can be achieved by git push.

Managing your project’s development

Git branches are easy to create and to eliminate, and are really useful when you need to work on an isolated copy of your work, whether that is to fix a bug or build a new feature. As it is almost always desirable to keep a master branch in a stable state, it is useful to offload development to at least one branch dedicated to that purpose. As the project becomes more complicated and involves several collaborators, branching strategies such as Gitflow provide a streamlined way to develop code. Choosing a branching strategy involves making several choices such as how long-lived or short-lived and how many different types of development branches the project should have, and whether one or more branches dedicated to released code should be provisioned. Which strategy to choose depends, among other considerations, on the scope of the project and the number of collaborators involved.

A basic Git feature which allows tracking important points in your development history is the concept of tags, which mark specific commits in an easily accessible way for future reference. A tag reference is similar to a branch reference except that it always points to the same commit. Using tags raises the issue of how they should be named. Although the name of a Git tag can in principle be anything you like, it makes sense to follow some convention in producing them to allow for information about the content of the tag to be instantly extracted from the tag name. You could use some rule based on the date of the commit but that would be superfluous as the commit object already includes this information. A very popular alternative is to use the rules set forth by semantic versioning. Tags that follow semantic versioning consist of three numbers X.Y.Z. An increment in each of those numbers signifies something about the state of the project. X corresponds to a major version which means that each new X marks a breaking change, one that is incompatible with previous versions. Y corresponds to a minor version which should be updated every time you add a new feature or functionality to a given major version. Z corresponds to a patch version which contains changes needed to resolve a bug. Just by reading these three numbers your project’s users can already know what a new version has to offer and whether to expect breaking changes.

To create a tag from the current state of a branch you can run

git tag -a v1.1.0 -m "version 1.1.0"

and to tag any commit

git tag -a v1.1.0 de17b1e -m "version 1.1.0"

where de17b1e is the commit’s short hash.

Tags are not transmitted to a remote by git push

but you can run

git push origin --tags

to do so.

Git for non-code text

Putting your manuscripts and other text-based files

under Git can be rewarding,

as long as you take some considerations into account.

While Git can track any file that you instruct it to,

with some file formats you are not getting the most out of Git.

An example that is relevant to many academics is Microsoft Word’s

native file format, DOCX.

Since a DOCX file is a compressed XML file,

diffing a DOCX file is not very informative

diff --git a/test.docx b/test.docx

index af57f2d..c0520bc 100644

Binary files a/test.docx and b/test.docx differ

While there are methods to improve what Git can show in diffs for different file types, better ways to write your manuscripts in the first place also exist, especially if you plan to source-control them (and you should). Since Git is meant to work best with simple text files, you should consider plain text formats. $\LaTeX$ offers some useful features, but it is more involved than needed in some circumstances. A simpler file format specification is Markdown which was initially designed as a text-to-HTML formatting syntax. The primary goal of Markdown is to enable writing human-readable text that can then be converted to HTML. Since its inception, many extensions have been added to the specification to allow for commonly used features such as math, citations, and code highlighting. As a result, Markdown has gained popularity as a format from which to convert text to many output formats. To go one step further it is recommended to use tools such as Jupyter notebooks or RMarkdown, both based on Markdown, to write scientific documents that involve computation accompanied by some explaining text.

Whatever text format you choose, following some best practices can improve the experience. Since Git is designed for code, it is not optimized out of the box to handle non-code text. Git will look for whole line differences and store them as such. That works well for code as each line is usually a self-contained command, or it should be. But a line of non-code text can be very long and changes of any size may trigger detection. If you do not separate each sentence to its own line, Git will treat whole paragraphs as a single line. If two people edit different sentences of a paragraph it will lead Git to treat those changes as a merge conflict. A simple way of mimimizing such conflicts is to break your text into lines of sentences or even short phrases. You can achieve this by pressing Enter to separate lines. The end result, whether rendered in HTML, PDF, DOCX, or another format, is not affected as these whitespace characters are not taken into account during conversion.

Another useful strategy involves breaking changes in your text into manageable chunks. Especially for long documents such as theses or books, it makes sense to split them into several different files, for example following their natural division into chapters. Even in a single-file case, it makes sense to work on sizable changes in separate branches. Doing so can allow you, for example, to always have a ready-to-share version, say in the master branch, while you keep working on not-yet-ready revisions in a separate branch. It can be also useful, especially if you ever wish to easily revert them, to make document-wide changes such as replacing a term with another in a single commit. In all cases, such strategies allow grouping of logically related changes, which makes the job of tracking and reverting them so much easier.

Outlook

By now we hope you should be convinced that Git is

- a better way to undo changes

- a better way to collaborate than emailing files back and forth

- a better way to share your code and other scientific work with the world

If the whole idea of merge requests reminds you of academic peer review, except in a more streamlined form, that is because the process is truly a perfect way to overhaul academic discourse. Although it’s not the usual practice in research, using hosting is a great way to invite other people to collaborate with you. For examples of how collaborative publications might look like see https://andrewgyork.github.io/ and this website in conjunction with its source repository. Even open source and completely free to publish and to read journals have been created using Git and hosted Git repositories, such as The Journal of Open Source Software (JOSS). In their announcement blog post the editors of JOSS cite the following passage from Buckheit and Donoho (1995):

An article about computational science in a scientific publication is not the scholarship itself, it is merely advertising of the scholarship. The actual scholarship is the complete software development environment and the complete set of instructions which generated the figures.

In fact, I envision a day when all scientific communication will be done through a service such as GitLab.

TL;DR

git init

git add .

git commit -m "Commit message"

git remote add origin git@gitlab.com:account/git-demo.git

git push -u origin master

then

git pull origin master

# Now make your edits

git add .

git commit -m "Commit message"

git push origin master

Acknowledgements

This article has heavily borrowed material from Software Carpentry’s tutorial on Git which can be found in https://swcarpentry.github.io/git-novice/.

References

Buckheit, Jonathan B., and David L. Donoho. 1995. “WaveLab and Reproducible Research.” In Wavelets and Statistics, edited by Anestis Antoniadis and Georges Oppenheim, 55–81. New York, NY: Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-2544-7_5.